Hearing the Music of Style: the Origin of my Folkloric Fantasy Novel

The first seed of Wick and Arrow that sprouted in my imagination was its style.

When I write a story, usually the characters are born first; they show me their conflict so I can make a plot out of it. Sometimes I envision a concept first and then discover the characters who fit into it. In this case I began with neither plot nor characters but style. I could hear it, taste it, feel it. I was like a composer who hears a melody first and later writes lyrics to it.

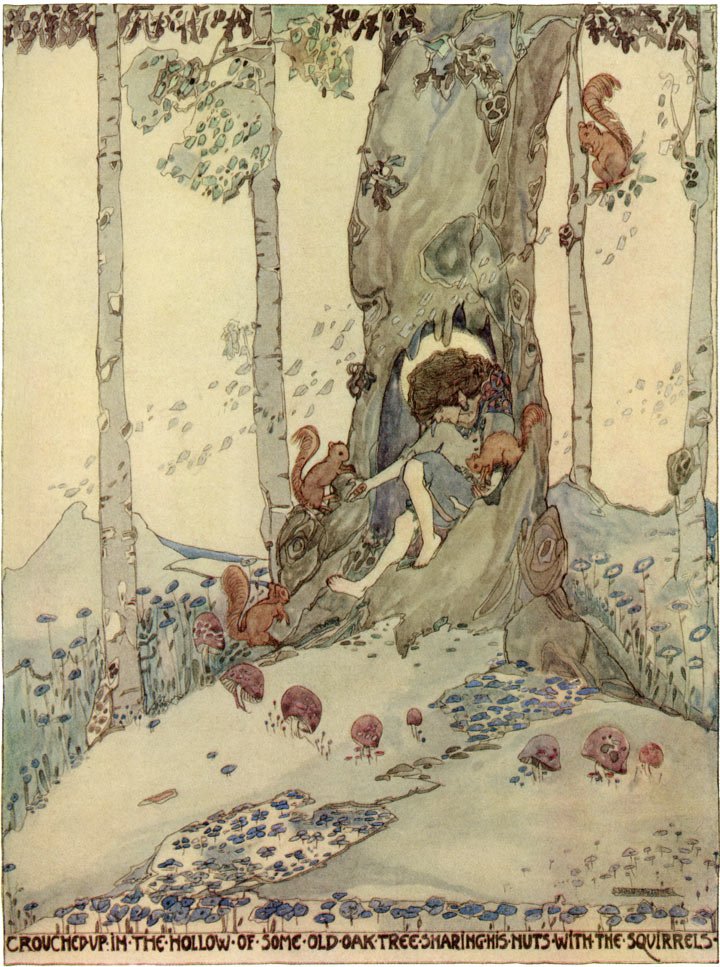

Jessie M. King illustration from Oscar Wilde’s House of Pomegranates

All throughout the process of writing Wick and Arrow, I would ask myself, “Are you being faithful to the style?” In other words, is the same music running through this story that you heard when it was conceived? Because the style was this particular piece of art’s most fundamental identity. If the characters did and said all the same things but the style changed, it would no longer be my own child but a changeling.

So what was this style?

Obviously it was high fantasy, because my imagination is essentially a fantastical universe in which undefined magic systems and lush dreamscapes collide and demand heroes. But I saw clearly and vividly (or rather heard; it was much more like music) that the style of this story was not epic fantasy. It was pre-epic: Hans Christian Andersen, George MacDonald, and Oscar Wilde, not Tolkien. The word that came to me was folkloric. Just a tale. A perilous but personal adventure in which, if the hero fails, no worlds will end except her own.

Those who know me will not be surprised to hear that the style was playful. I’m someone in whom the qualities of childlike wonder, discovery, and playfulness overrun everything properly adult. To the despair of my mother, I am “completely unpractical.” Children’s writing, in addition to poetry, has most often been where I’m able to say what I have to say, following Madeleine L’Engle’s advice, “You have to write the book that wants to be written. And if the book will be too difficult for grown-ups, then you write it for children.”

At the same time, I distinctly felt that this story was not for children. The music of the style was also philosophical, conceptual, psychological—mature. But playfully mature. Playing with language, playing with intellectual constructs, playing with the wry gravitas of the folktale in a way that felt simultaneously childlike and grown up. It was a twist on Madeleine L’Engle: If the book will be too difficult for grown-ups, write it for the inner child the grown-ups have silenced because they’re terrified of the truth it will blurt out if they let it.

“If the book will be too difficult for grown-ups, write it for the inner child the grown-ups have silenced because they’re terrified of the truth it will blurt out if they let it.”

It was only later, when I met the characters of Wick and Arrow, that I understood why no other style could adequately tell their story. My characters said, “Mary, write a fairytale for adults. Make it so simple a child could understand it, but write it for grown ups who are scared of being childlike because it hurts too much. Make them listen to our story anyway, because they need to know what happens to us. And maybe we can help them face their fears.”

So I did. Or at least, I hope I did. I said yes to the challenge, and I tried.