In Defense of Escapism: Tolkien’s Principles of Fantasy

During college, I spent several hoarse, sweaty summers as a day-camp counselor. One day during counselor training, our supervisors introduced an expert who had devised her own system of classifying personality types. Reading off twelve or so lists of traits, the woman instructed us to move to different sections of the room based on which description most closely matched our own.

I wasn’t really paying attention, of course, but somehow I managed to hear the description that struck me as a patented portrait of myself. When we self-segregated, I moved quite confidently to my rightful place. No sooner had I arrived than my confidence began to wane.

I found myself in a group with only two other people: my own sister, and a pale girl who did not look at us but muttered to herself and chewed on the ends of her hair.

The expert went around the room, naming us as Adam named the animals: the Actives, the Bashfuls, the Easy-Goings, the Entertainers, and so on. Everyone laughed, recognizing the truth in what she said about each type. My anxiety increased.

The expert saved our little trio for last. She paused. I unconsciously took a step away from Pale Muttering Girl. Looking straight into my eyes with a gaze of pity, curiosity, and thinly-veiled fear, the expert announced, “This is one of the most unique personality types I have discovered in all my years of research. They are the hardest to understand. They often seem to be in their own world, which is difficult to penetrate.”

“These… are the Highly Creative Escapists.”

The room fell silent as the others stared. It’s not true! I shouted in my imagination. I’m not an escapist!

I lowered my eyelids and suddenly found myself atop a wooden platform in Salem as my neighbors flung ‘Witch!’ at me.

Despite the unpleasantness of being so ruthlessly unmasked before my peers, I subsequently developed a certain confidence in my identity as an escapist. Perhaps it was the inclusion of flattering adjectives that blunted the term’s pejorative edge. I felt that the Highly Creative Escapists should start some sort of social movement, defending our right to mildly disdain the world in which we live and slip away to a better, imaginary one.

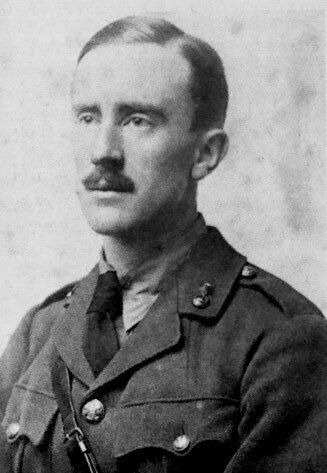

Then I realized that such a social movement already existed. It began at Oxford more than sixty years ago, and its founder was J.R.R. Tolkien.

In Tolkien’s definitive essay “On Fairy-Stories,” he names “Escape” as one of the main functions of fantasy literature. Attempting to rescue the term from disparaging usages, Tolkien insists, “Evidently we are faced by a misuse of words, and also by a confusion of thought. Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if, when he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls?” Tolkien makes a distinction between his understanding of ‘escapism’ and an infantile refusal to acknowledge the real world or engage its complexities: “In using escape in this way, the critics have chosen the wrong word, and, what is more, they are confusing, not always by sincere error, the Escape of the Prisoner with the Flight of the Deserter.” The deserter flees because he is afraid. The prisoner escapes because he knows that prison is not where he is meant to be.

Some may take issue with Tolkien’s comparison of the real world to a prison. Isn’t this perspective terribly negative? Doesn’t it lead to inaction with regards to ‘working toward a better tomorrow’?

To understand Tolkien’s prison analogy, it may help to consider the context in which he began to write ‘escapist’ literature. Commissioned in the Lancashire Fusiliers during WWI, Tolkien began writing “my nonsense fairy language” (“Letter to Edith Bratt,” 2 March 1916) amidst the miserable conditions of army life. During the next world war, he writes about his experience to his son Christopher, who finds himself in similar circumstances: “I first began to write the ‘History of the Gnomes’ in army huts, crowded, filled with the noise of gramophones—and there you are in the same prison. May you, too, escape—strengthened” (“To Christopher Tolkien,” 30 April 1944).

And in another letter to Christopher, a week later: “I sense amongst all your pains (some merely physical) the desire to express your feeling about good, evil, fair, foul in some way: to rationalize it, and prevent it just festering. In my case it generated Morgoth and the History of the Gnomes. Lots of the early parts of which… were done in grimy canteens, at lectures in cold fogs, in huts full of blasphemy and smut, or by candle light in bell-tents, even some down in dugouts under shell fire. It did not make for efficiency and present-mindedness, of course, and I was not a good officer” (6 May 1944). In this excerpt, we begin to understand ‘escapism’ as an act of courage, a way of holding onto one’s humanity amidst conditions which threaten it.

A month later, Tolkien explicitly uses the word escapism in a further attempt to convince his son to write as a means of survival: “So I took to ‘escapism’: or really transforming experience into another form and symbol with Morgoth and Orcs and the Eldalie (representing beauty and grace of life and artefact) and so on; and it has stood me in good stead in many hard years since…” (“From a letter to Christopher Tolkien,” 10 June 1944). Tolkien the dreamer, the lover of languages, trees, and gardens, is not destroyed by Tolkien the soldier. Rather, in the brutal ugliness of trench warfare, a defiant beauty emerges which will increasingly consume Tolkien’s life and imagination.

Thus, Tolkien’s defense of escapism. But what of my own? What right does a middle-class American millennial have to ‘Escape’ (of which, in its pejorative sense, millennials are so often accused)? Why did this propensity emerge in the midst of a comparatively happy childhood? Was there something morbid in my frequent childhood prayer, “Dear God if you can do anything, please make Narnia real”?

In “On Faerie Stories,” Tolkien describes the need for ‘Escape’ as a result of the human condition. We are finite beings, and our limitations grate on us. We wish we could fly. We wish we could converse with animals. We wish we could shoot spider-webs from our wrists and swing from skyscraper to skyscraper.

Hence, our perennial fascination with magic and the whole realm of alternate realities affording the possibility of power, beauty, and adventure beyond what our own world can provide.

At the same time, escaping the constraints of reality through imagination never means denying or abandoning reality. The thrill of escapism hinges on the distinction between the imaginary and the real: “For creative Fantasy is founded upon the hard recognition that things are so in the world as it appears under the sun; on a recognition of fact, but not a slavery to it. … If men really could not distinguish between frogs and men, fairy-stories about frog-kings would not have arisen” (Tolkien, “On Faerie Stories”).

Not only does the escapism of fantasy not deny the value of the real world, it actually seeks to uphold and nurture it. “For the story-maker who allows himself to be ‘free with’ Nature can be her lover not her slave. It was in fairy-stories that I first divined the potency of the words, and the wonder of the things, such as stone, and wood, and iron; tree and grass; house and fire; bread and wine” (ibid). Fantasy helps us fall back in love with a world we have forgotten to see. A fascination with fantastic beasts opens our eyes to the delightful creatures around us. Aragorn son of Arathorn helps us imagine the possibility of moral integrity in a political leader. Ents teach us to hug trees.

Far from crippling our desire to transform the world around us for the good, escapist fantasy should inflame that desire. In an example so typical of his distaste for industrial ugliness, Tolkien explains: “For a trifling instance: not to mention (indeed not to parade) electric street-lamps of mass-produced pattern in your tale is Escape” (ibid). Though the escapist remains painfully aware that he is doomed to walk streets lit with functional, economical, unattractive lamps, “He does not make things (which it may be quite rational to regard as bad) his masters or his gods by worshipping them as inevitable, even ‘inexorable.’ And his opponents, so easily contemptuous, have no guarantee that he will stop there: he might rouse men to pull down the street-lamps. Escapism has another and even wickeder face: Reaction.”

Beware the Highly Creative Escapists. We may seem dreamy, distracted, or downright disillusioned. But this is our secret: we are too in love with the world to let it remain as it is. And we have found our allies.